The Artist takes a risky and intriguing concept, and attacks it with an overwhelming passion for cinema and a great sense of fun. In the process, the filmmakers create an innocent crowd-pleaser most contemporary blockbusters can’t hold a candle to for entertainment value or charm.

There was a real danger that making a silent movie in for 21st Century could have been a gimmicky one-note joke, even an out-and-out disaster. While the filmmakers draw inspiration from the past and the project is inevitably nostalgia-laden, the decision to make a silent film in 2011 is really a radical act, and on this account The Artist could not afford to be even a partial failure. Thankfully the film has been beautifully conceived and executed, from the screenplay through the casting, production design, cinematography, acting and editing.

If silence is a virtue, the virtue in this case is to effect a return to the essential qualities of cinema as a unique artform, distinct from literature, and in particular from television. Without sound, the filmmakers are forced to rely on visual storytelling: the power of the close-up, the composition of the frame, the rhythm of the editing, a sequence of moving images captured through a lens, no more and no less. Consequently everything about this movie is bold.

The plot will be familiar stuff to classic movie fans, the story of a silent movie star at the peak of his career who finds himself on the fast-track to down-and-out, going from man-of-the-moment to obsolete relic in a heartbeat, with the advent of talking pictures. Meanwhile, a young ingénue with a voice rises to stardom. Expect a rise and fall complete with dancing elephants and burning filmstock, an abundance of laughs, and of course a romance.

Perhaps the most unexpected delight of The Artist is that it is so playful, thanks in no small part to director Michel Hazanavicius, who had so much fun with Dujardin on the OSS117 series of French spy-spoofs. The filmmakers play endlessly with the muted concept, replete with sight-gags (including a backstage sign reading ‘Silence Please’), inter-titles such as ‘we need to talk’, and at one point a wickedly clever use of the single word “Bang!” The few occasions where synchronized sounds are used in the film, in a dream sequence and in the very final scene, are hilarious.

Countless times The Artist descends into melodrama without losing its touch: everything is Dramatic, but nothing is overdone. With a tone that is frequently airy light, warm and almost giddy, where Scorcese’s Hugo resorts to slapstick The Artist offers a more sophisticated take on physical comedy: it is all about the art of the gag. Watch closely and you will see what a fantastic grasp the filmmakers and the editor in particular have on that key concept, ‘comedy is timing’. In this respect, the editing is pitch-perfect, each sequence a masterclass.

Of course movie is not silent in the purest sense; there is music throughout – silent films just aren’t very engaging without it, and there are severe technical challenges to exhibiting a soundless movie. During the few dead-silent moments, you quickly become aware that cinemas are not sound-proof, especially if there is a thundering bassy score to compete with from the actioner next door. I have seen The Artist twice, once in a packed cinema where the audience reaction added its own element to the soundtrack, and once in a deserted cinema which changed the experience slightly. Though it was excellent both times this film is a special joy to see with a full theatre audience, as it is so much a film about audiences.

The opening sequence, which take place at the premiere of George Valentin’s latest film, is particularly powerful. It had to be. It is here the film lays out a contract with the audience and tells them what they can expect from the rest of the movie. To this end we are assured of a degree of complexity to the storytelling, lush cinematography, and above all entertainment. I loved the opening shots, which use the silver screen to create the centerpiece of a multi-leveled scenario, dividing the theatre where an engrossed audience laps up George’s every flourish, and the backstage, where the actors and filmmakers anxiously await the moment they can step forward to take their bows.

George’s film, an adventure-romance, is excellently constructed and camply hilarious, accompanied by audience reaction playing in beautiful shots, with perfect composition and rich depth. As the film-within-a-film reaches a frenzy of suspense, the filmmakers cut to the expressions of the audience, implying a delightful surprise on the screen but leaving the details to our imagination. Here as in other places, it’s all about the faces. Successful portrayals of cinemas on film can be especially powerful (think Cinema Paradiso) and this stands with the best of them as an entirely worthy love letter to cinema.

The grandiose cinematography is frequently reminiscent of Citizen Kane, not only through the use of outmoded multi-layered montages, but through the use of contrast – of scale, of light and dark, of foreground and background. It really stands on a par visually with that film. When it is not light and jazzy, the music provides an emotive and sensationalist score that might have come from the 1940s, there’s excess a-plenty but handled skillfully enough that it never grates.

As a film of faces, we are given many to enjoy: notably James Cromwell as George’s faithful chauffer, and John Goodman as a growling teddy-bear of a producer. But the casting masterstroke has to be the pairing of Dujardin and Bejo (as rising star Peppy Miller) for the beguiling leads. Both actors bring dazzling physical presences and offer an abundance of radiant million-dollar smiles, nuanced glances and charismatic, high energy performances. They are a pleasure to watch.

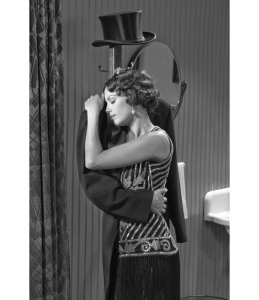

This is a very physical film, reveling in the poetry of motion, and almost has the feeling of a dancical – a fascinating genre of film that exists mostly in my imagination. We have a great routine involving a ‘disembodied’ pair of legs, and a beautiful scene where Peppy sneaks into George’s dressing room and crafts a fantasy lover out of his coat and top-hat. Describing it cannot do it justice, it really has to be seen, but it is moving and funny and exquisite all at once. Two other dance scenes act as bookends for the romance between Peppy and George. And there is an Oscar-worthy turn from little dog Uggie – refusing to be outshone even by Dujardin he hams it up with the best of them, bearing more than a passing resemblance to Asta, the terrier-star in Bringing Up Baby, Topper and many other comedy classics.

Light as it is, is the film shallow? I don’t think so. But it is a simple pleasure, and a bona-fide melodrama, dishing up a naïve love story in which our heroine loves our hero from the beginning through to end. Peppy is the emotional core of the film, and the tension between her and Valentin is a factor of his wounded pride. He is a man who really doesn’t exist without an audience. When she goes to watch his final flop of a movie and it moves her to tears, we really believe she is in love with him, and wish she could be audience enough. After a fire in which George is nearly killed, she goes to visit him in the hospital, clinging to the only piece of film he saved from the fire, outtakes from a dance sequence that tell the truth about his heart.

As two Oscar-nominated films looking back reverentially at the roots of cinema, comparisons with Hugo are inevitable. Simply put, The Artist outshines Scorcese’s movie. Where Hugo looks back in a studied way at they hey-day of the Lumieres and Melies contrasting these with the advent of 3D, The Artist takes the opposite tack to suggest that audiences have not changed as much as films have since the heyday of the silent era. *UPDATE* Pablo Berger’s gorgeous 2012 silent movie, Biancanieves (Snow White) makes a more interesting comparison and is arguably ‘purer’, less meta and self-referential than the Artist.

Is this a film for the ADD generation? Difficult to say, but anyone who truly loves the movies will find much to enjoy here, no effort or training required. Hollywood, let this be a lesson: if it can effect a return to well-crafted, thoughtful, populist filmmaking, then silence really can be a virtue.